Old theme, original execution. Excellent!

torsdag 6 december 2012

lördag 1 december 2012

Back from the Comics Store, Nov 2012b Edition

In my defense, not only had my monthly comics come in, they were also having a bit of a sale.

I'm hoping for a long, peaceful Christmas vacation to read them all. (Not that that'll happen.)

fredag 30 november 2012

My t-shirts, part 55: Uncle Sam

The Uncle Sam two-part Vertigo series had gorgeous art by Alex Ross, but suffered from a major plotline weakness – I already know enough of U.S. history that I'm not exactly surprised, baffled or provoked by being told about some of the less savory things that nation has done over the years. So it was a kind of "Meh" book IMO.

But the art is still gorgeous.

onsdag 21 november 2012

tisdag 20 november 2012

The Art of Comics. A Philosophical Approach. Edited by Aaron Meskin and Roy T Cook

I've always been a bit suspicious when people from the so-called "high culture" sphere descend to the comics sphere to apply its tools and sensibilities on it. Basically, this distrust is based on a bunch of instances where I've seen people apply not so much tools and sensibilities as 1) prejudices and ignorance, and 2) political opinionating.

Now, I've got nothing against political opinionating per se; in fact, I've been known to engage in it myself from time to time, but when you let it take over what was supposed to be an essay or article about a particular comic, you sort of lose the purpose of writing about that comic, don't you? And, if you're arguing that Donald Duck comics are inherently imperialistic, or that The Phantom is inherently racist, you're just putting forth your own prejudices and ignorance, anyway.

The people – or, more precisely, the philosophers – behind the essays in The Art of Comics aren't prejudiced and ignorant, however. Instead, they seem genuinely interested in, and knowledgeable about, the subjects they address in 10 rather diverse essays. I disagree with them on a lot of things, but that's not because they're ignorant or stupid, it's just because I think they got some things wrong, and that could happen to anybody (even myself on occasion, I must confess).

I'll address my problems with some of the analyses in the book, but I'd of course encourage anyone to read the book themselves and form their own opinion. Here goes:

Chapter 1: Redefining Comics, by John Holbo

… argues that the definition of comics should include daily panels, like the Family Circus. His reasoning seems to be that comics evolved out of Punch-style cartoons, that it's to hard to exclude works like Michelangelo's roof to the Sixtine Chapel etc. with McCloud's definition, and that even one-panel cartoons are sequential; a sequence of one that implies several different moment within itself.

I can't agree with Holbo's reasoning. There is a clear difference between having to imply different moments within a panel and being able to choose to do so if you want to, because it furthers your narrative better than doing so in two or more panels. And we most certainly don't have to let the Family Circus into the comics family just because the Bayeux Tapestry doesn't look like ordinary comics, that's not a logical reason.

Chapter 2: The Ontology of Comics, by Aaron Meskin

… addresses the definition of comics from a different angle; that by defining them as multiple works of art, you can get past the problems of other definitions (like McCloud's) with excluding certain works of art from the category of comics. "[C]omics and graphic novels are typically multiple works of art rather than mere copies, and in virtue of this they allow for simultaneous but spatially-distinct and unconnected reception points. In other words, different people can experience them at the same time and in significantly different locations."

I think both Holbo and Meskin are needlessly complicates the issue of definitions. If they'd separate the form of comics from the published works, they'd probably be able to escape some of the problems with the definitions that they now have to jump through all sorts of rhetorical hoops to try to solve. Thus, the original pages that would be published in the legendary Action Comics issue were in the comics form, and the printed pages were also. And honestly, the Sixtine Chapel roof isn't really comics at all, and it's really not all that hard to exclude it even from a McCloud-ish definition. What we have to realize is that definitions – at least in the humanities – tend to get very fuzzy at the edges when you look at them closely enough. The solution to that isn't generally to add more complexity to the definition that creates new fuzzy areas while making it more unwieldy, but to apply a modicum of common sense when making a judgement of what to include and exclude at those fuzzy edges of the definition.

Chapter 3: Comics and Collective Authorship, by Christy Mag Uidhir

… looks at the problem of who should be counted as author in collectively created works with an editor, writer, penciller, inker, colorist, and a letterer. Uidhir's solution is to a) use the formula "authorship-of-a-work-as-'X'" rather than "authorship-of-a-work", b) try to decide whether the contribution a person makes is sufficiently substantive to him/her count as one of the authors.

I really don't think those conclusions warrant the formal logic that precedes them as Uidhir builds his case; they're a little bit too easy to reach by commonsense reasoning.

Now, I've got nothing against political opinionating per se; in fact, I've been known to engage in it myself from time to time, but when you let it take over what was supposed to be an essay or article about a particular comic, you sort of lose the purpose of writing about that comic, don't you? And, if you're arguing that Donald Duck comics are inherently imperialistic, or that The Phantom is inherently racist, you're just putting forth your own prejudices and ignorance, anyway.

The people – or, more precisely, the philosophers – behind the essays in The Art of Comics aren't prejudiced and ignorant, however. Instead, they seem genuinely interested in, and knowledgeable about, the subjects they address in 10 rather diverse essays. I disagree with them on a lot of things, but that's not because they're ignorant or stupid, it's just because I think they got some things wrong, and that could happen to anybody (even myself on occasion, I must confess).

I'll address my problems with some of the analyses in the book, but I'd of course encourage anyone to read the book themselves and form their own opinion. Here goes:

Chapter 1: Redefining Comics, by John Holbo

… argues that the definition of comics should include daily panels, like the Family Circus. His reasoning seems to be that comics evolved out of Punch-style cartoons, that it's to hard to exclude works like Michelangelo's roof to the Sixtine Chapel etc. with McCloud's definition, and that even one-panel cartoons are sequential; a sequence of one that implies several different moment within itself.

I can't agree with Holbo's reasoning. There is a clear difference between having to imply different moments within a panel and being able to choose to do so if you want to, because it furthers your narrative better than doing so in two or more panels. And we most certainly don't have to let the Family Circus into the comics family just because the Bayeux Tapestry doesn't look like ordinary comics, that's not a logical reason.

Chapter 2: The Ontology of Comics, by Aaron Meskin

… addresses the definition of comics from a different angle; that by defining them as multiple works of art, you can get past the problems of other definitions (like McCloud's) with excluding certain works of art from the category of comics. "[C]omics and graphic novels are typically multiple works of art rather than mere copies, and in virtue of this they allow for simultaneous but spatially-distinct and unconnected reception points. In other words, different people can experience them at the same time and in significantly different locations."

I think both Holbo and Meskin are needlessly complicates the issue of definitions. If they'd separate the form of comics from the published works, they'd probably be able to escape some of the problems with the definitions that they now have to jump through all sorts of rhetorical hoops to try to solve. Thus, the original pages that would be published in the legendary Action Comics issue were in the comics form, and the printed pages were also. And honestly, the Sixtine Chapel roof isn't really comics at all, and it's really not all that hard to exclude it even from a McCloud-ish definition. What we have to realize is that definitions – at least in the humanities – tend to get very fuzzy at the edges when you look at them closely enough. The solution to that isn't generally to add more complexity to the definition that creates new fuzzy areas while making it more unwieldy, but to apply a modicum of common sense when making a judgement of what to include and exclude at those fuzzy edges of the definition.

Chapter 3: Comics and Collective Authorship, by Christy Mag Uidhir

… looks at the problem of who should be counted as author in collectively created works with an editor, writer, penciller, inker, colorist, and a letterer. Uidhir's solution is to a) use the formula "authorship-of-a-work-as-'X'" rather than "authorship-of-a-work", b) try to decide whether the contribution a person makes is sufficiently substantive to him/her count as one of the authors.

I really don't think those conclusions warrant the formal logic that precedes them as Uidhir builds his case; they're a little bit too easy to reach by commonsense reasoning.

Chapter 4: Comics and Genre, by Catharine Abell

… tries to define what is genre in comics but gets a bit lost in all the categories and terminology, proposing that "genres are sets of conventions that have developed as means of adressing particular interpretative and/or evaluative problems, and have a history of co-instantation within a community, such that a work's belonging to some genre generates interpretative and evaluative expectations among the members of that community. To belong to some genre, a work must be produced in a community in which its constitutive conventions have a history of co-instantiation and must be produced in accordance with some subset of those conventions that is sufficient to distinguish the set of conventional at issue from all other sets of conventions that have developed as means of addressing interpretative and/or evaluative concerns and have a history of co-instantiation within the community in which the work was produced. A work is produced in accordance with a convention if and only if it both has features of the type picked out by the convention at issue and its maker gave the work those features so that the convention would apply to it."

Not only is that simply too convoluted, I really don't understand why a work couldn't be assigned to a genre based on its own qualities, regardless of what intentions the creator had when creating it. Basically, to me, Abell's chapter (like Uidhir's) addresses what is pretty much a non-problem.

… tries to define what is genre in comics but gets a bit lost in all the categories and terminology, proposing that "genres are sets of conventions that have developed as means of adressing particular interpretative and/or evaluative problems, and have a history of co-instantation within a community, such that a work's belonging to some genre generates interpretative and evaluative expectations among the members of that community. To belong to some genre, a work must be produced in a community in which its constitutive conventions have a history of co-instantiation and must be produced in accordance with some subset of those conventions that is sufficient to distinguish the set of conventional at issue from all other sets of conventions that have developed as means of addressing interpretative and/or evaluative concerns and have a history of co-instantiation within the community in which the work was produced. A work is produced in accordance with a convention if and only if it both has features of the type picked out by the convention at issue and its maker gave the work those features so that the convention would apply to it."

Not only is that simply too convoluted, I really don't understand why a work couldn't be assigned to a genre based on its own qualities, regardless of what intentions the creator had when creating it. Basically, to me, Abell's chapter (like Uidhir's) addresses what is pretty much a non-problem.

Chapter 5: Wordy pictures: Theorizing the Relationship between Image and Text in Comics, by Thomas E. Wartenberg

… argues that the image is the most important part of the comic as it doesn't need words to be comics, and it's hard to disagree with that, but it's also hard to see it as an important breakthrough. He also doesn't want to exclude single-panels from the comics definition, but again the reasons for doing so seem a bit thin. Wartenberg points to how The Yellow Kid is generally held to be the first newspaper strip besides being a single panel comic, but that something "is held to be" something by some is a pretty poor argument for defining it that way.

Again, I think something would be gained from separating the definition of the comic form – basically a sequence of pictures (intentionally) creating a narrative – from the issue of whether some published work should count as a "comic" or not. For example, The Far Side is a cartoon that occasionally used the comics format (like with the cow walking up to the farmer's door, ringing the doorbell, and then returning to grazing before the bewildered farmer opened the door), whereas Peanuts is a comic strip that occasionally was comprised of a single panel. While the strip wasn't in a comics but a cartoon format in those instances, there's little doubt that Peanuts was a comic strip overall.

… argues that the image is the most important part of the comic as it doesn't need words to be comics, and it's hard to disagree with that, but it's also hard to see it as an important breakthrough. He also doesn't want to exclude single-panels from the comics definition, but again the reasons for doing so seem a bit thin. Wartenberg points to how The Yellow Kid is generally held to be the first newspaper strip besides being a single panel comic, but that something "is held to be" something by some is a pretty poor argument for defining it that way.

Again, I think something would be gained from separating the definition of the comic form – basically a sequence of pictures (intentionally) creating a narrative – from the issue of whether some published work should count as a "comic" or not. For example, The Far Side is a cartoon that occasionally used the comics format (like with the cow walking up to the farmer's door, ringing the doorbell, and then returning to grazing before the bewildered farmer opened the door), whereas Peanuts is a comic strip that occasionally was comprised of a single panel. While the strip wasn't in a comics but a cartoon format in those instances, there's little doubt that Peanuts was a comic strip overall.

Chapter 6: What's So Funny? Comic Content in Depiction, by Patrick Maynard

… basically argues that humor strips signal their ephemeral content by being published on the comics page and by being drawn in a simple, cartoony style.

… basically argues that humor strips signal their ephemeral content by being published on the comics page and by being drawn in a simple, cartoony style.

Chapter 7: The Language of Comics, by Darren Hudson Hick

… treats panels as a basic unit in the not language but syntax of comics. I do think Hick, as a philosopher, is perhaps a bit too eager to try and understand comics as a language akin to natural languages, when it is in fact anything but, but he reaches the pretty reasonable conclusion that "although discussing comics as a natural language is perhaps a strech, it seems not unreasonable to talk of them as being language-like – as constituting a pseudo-language – operating in many ways like a natural language." Like I said, not unreasonable, but why treat comics as a "pseudo-languages" instead of just comics? Why not just analyze how comics actually achieve the effects they achieve?

… treats panels as a basic unit in the not language but syntax of comics. I do think Hick, as a philosopher, is perhaps a bit too eager to try and understand comics as a language akin to natural languages, when it is in fact anything but, but he reaches the pretty reasonable conclusion that "although discussing comics as a natural language is perhaps a strech, it seems not unreasonable to talk of them as being language-like – as constituting a pseudo-language – operating in many ways like a natural language." Like I said, not unreasonable, but why treat comics as a "pseudo-languages" instead of just comics? Why not just analyze how comics actually achieve the effects they achieve?

Chapter 8: Making Comics into Film, by Henry John Pratt

… makes the somewhat silly argument that comics are especially good to adapt into movies because they unlike paintings are narrative, and unlike literature works with pictures, and are already cut into scenes just like films are.

… makes the somewhat silly argument that comics are especially good to adapt into movies because they unlike paintings are narrative, and unlike literature works with pictures, and are already cut into scenes just like films are.

(There are a couple of chapters more, but I didn't find them sufficiently interesting to take extensive notes on them.)

So, there you have it. Quite obviously, I have a lot of reservations about the analyses and conclusions put forth in this book, but I applaud the authors and editors for the effort, and would encourage anybody with a serious interest in the comics medium to read it and make up their own mind.

… But I do think you'll actually get way more insights about the comics medium by reading Scott McCloud's Understanding Comics and Making Comics. Seriously.

… But I do think you'll actually get way more insights about the comics medium by reading Scott McCloud's Understanding Comics and Making Comics. Seriously.

måndag 19 november 2012

I did this! This summer...

... while moving into a new house and trying to get myself and my comics, books etc. settled there... There have been periods of my life during which I've felt less stressed-out.

|

| "You're a disgrace to the Army! I want to see superheroes!" A tie-in with the Avengers movie (which was excellent, btw). |

|

| "Now, before we start, has everyone been to the bathroom?" |

söndag 18 november 2012

Brant Parker & Johnny Hart: The Wizard of Id. Dailies and Sundays 1972

In my teens, I read quite a lot of collections of daily strips. There were these cheap pocketbook collections of B.C., The Wizard of Id, Peanuts, etc, that I used to buy when we went from my small town home of Ånge to visit relatives in a real city like Östersund, which had proper bookstores. I loved Peanuts, and the rest of them were usually OK, but not up to the same standards – but hey, they were comics, so I read 'em.

Occasionally, my love of comics would lead me into the realm of cultural discourse – the gorgeous artwork of someone like Neal Adams would inspire an interest in fine art in general, sometimes the prominent culturati of the time would discuss comics (unfortunately rarely with any particularly impressive amount of knowledge about the subject), or some left-oriented critic would put out an article or a book condemning the USA-produced trash that was supposedly indoctrinating innocent kids into a capitalistic, imperialistic and evil worldview.

I remember reading a particularly galling review of a collection of comics dailies, where the reviewer complained that it was tiresome to read the whole collection because it got repetitive and the strips probably weren't intended to be collected into a book like that. First of all: well, duh – they were intended to be published as daily strips in a newspaper; collecting them was a bonus for people who liked the strip. Second, I don't recall what strip it was, but if it was Peanuts, the reviewer must have been an idiot, because any chance to read Peanuts strips is a treat to be savored.

And finally, the reviewer was an idiot, because how bloody hard can it be to simply put the book away and do something else for a while, and then come back and pick it up to read some more when you feel like it? After all, you can probably manage to do so with novels of short story collections, so how hard can it be to do the same when the book contains comic strips instead? Good grief.

Anyway, what this rambling leads up to is my appreciation for today's quite excellent trend of collecting old strips in complete editions, and more precisely Titan Books' The Wizard of Id. Dailies and Sundays 1972.

The Wizard of Id wasn't exactly one of my favorites; partly because the art wasn't as clean or pretty as in some other strips, partly because the jokes just didn't seem quite as funny. A lot of them were about how fat, ugly and unpleasant the Wizard's wife was, and I'd already read plenty enough of that kind of jokes to be kind of tired of them.

Re-reading the strip today, I have to say that I agree with my younger self. Apart from the "ugly wife" strips, there are strips with puns, strips with "short" jokes about the diminutive king of Id, booze jokes about the alcoholic court jester Bung, and contemporary jokes about women's lib etc. Some of the jokes work, some don't, but generally, the strip never really takes off. Like B.C. and Peanuts, The Wizard of Id was considered a "sophisticated" strip in those days. The term referred to how that sort of strips worked with words and small effects instead of "bigfoot" cartooning (of which Beetle Bailey would be the foremost example), slapstick and wild, grandiose, physical humor, and for that purpose, I suppose I'll go along with it. But Parker et al – and most of the other strips in that tradition – while often clever in their puns, put-downs etc, never reached the level of sophistication that Charles Schulz managed to achieve, really creating Art by sublimating his neuroses, anxieties and aspirations into a cohesive, captivating whole.

Nevertheless, my hat's off to Titan Books for collecting this bit of comics history into a nice, appealing package, and I hope they continue to do so, even though I won't recommend it. I would, however, recommend them to remove the annoying "JohnnyHartStudios.com" sticker that is in Every-Bloody-Strip mucking them up graphically and distracting the reader from what's important: the actual strips. (If they could also get the copyright stickers out of the panels and into the gutters instead, and preferably also make it just a smidgeon smaller, that would also be appreciated.)

Oh, and it does get a bit tiresome to read long stretches of the strip, because it is kind of scratchy in its artwork and kind of repetitive in its humor. It probably wasn't intended to be read like this, strip after strip after strip in a whole book.

But you know what? That's not really a problem. You can read a month or so at a time, put the book away for a couple of hours or a day or two, and then return to read some more.

That is, if you're not too stupid to figure that out.

Occasionally, my love of comics would lead me into the realm of cultural discourse – the gorgeous artwork of someone like Neal Adams would inspire an interest in fine art in general, sometimes the prominent culturati of the time would discuss comics (unfortunately rarely with any particularly impressive amount of knowledge about the subject), or some left-oriented critic would put out an article or a book condemning the USA-produced trash that was supposedly indoctrinating innocent kids into a capitalistic, imperialistic and evil worldview.

I remember reading a particularly galling review of a collection of comics dailies, where the reviewer complained that it was tiresome to read the whole collection because it got repetitive and the strips probably weren't intended to be collected into a book like that. First of all: well, duh – they were intended to be published as daily strips in a newspaper; collecting them was a bonus for people who liked the strip. Second, I don't recall what strip it was, but if it was Peanuts, the reviewer must have been an idiot, because any chance to read Peanuts strips is a treat to be savored.

And finally, the reviewer was an idiot, because how bloody hard can it be to simply put the book away and do something else for a while, and then come back and pick it up to read some more when you feel like it? After all, you can probably manage to do so with novels of short story collections, so how hard can it be to do the same when the book contains comic strips instead? Good grief.

Anyway, what this rambling leads up to is my appreciation for today's quite excellent trend of collecting old strips in complete editions, and more precisely Titan Books' The Wizard of Id. Dailies and Sundays 1972.

The Wizard of Id wasn't exactly one of my favorites; partly because the art wasn't as clean or pretty as in some other strips, partly because the jokes just didn't seem quite as funny. A lot of them were about how fat, ugly and unpleasant the Wizard's wife was, and I'd already read plenty enough of that kind of jokes to be kind of tired of them.

Re-reading the strip today, I have to say that I agree with my younger self. Apart from the "ugly wife" strips, there are strips with puns, strips with "short" jokes about the diminutive king of Id, booze jokes about the alcoholic court jester Bung, and contemporary jokes about women's lib etc. Some of the jokes work, some don't, but generally, the strip never really takes off. Like B.C. and Peanuts, The Wizard of Id was considered a "sophisticated" strip in those days. The term referred to how that sort of strips worked with words and small effects instead of "bigfoot" cartooning (of which Beetle Bailey would be the foremost example), slapstick and wild, grandiose, physical humor, and for that purpose, I suppose I'll go along with it. But Parker et al – and most of the other strips in that tradition – while often clever in their puns, put-downs etc, never reached the level of sophistication that Charles Schulz managed to achieve, really creating Art by sublimating his neuroses, anxieties and aspirations into a cohesive, captivating whole.

|

| Actually, I think this is a pretty decent joke, as jokes go. But this is as good as it gets. |

Nevertheless, my hat's off to Titan Books for collecting this bit of comics history into a nice, appealing package, and I hope they continue to do so, even though I won't recommend it. I would, however, recommend them to remove the annoying "JohnnyHartStudios.com" sticker that is in Every-Bloody-Strip mucking them up graphically and distracting the reader from what's important: the actual strips. (If they could also get the copyright stickers out of the panels and into the gutters instead, and preferably also make it just a smidgeon smaller, that would also be appreciated.)

Oh, and it does get a bit tiresome to read long stretches of the strip, because it is kind of scratchy in its artwork and kind of repetitive in its humor. It probably wasn't intended to be read like this, strip after strip after strip in a whole book.

But you know what? That's not really a problem. You can read a month or so at a time, put the book away for a couple of hours or a day or two, and then return to read some more.

That is, if you're not too stupid to figure that out.

lördag 17 november 2012

Mark Waid, Paolo Rivera & Marcos Martin: Here Comes… Daredevil, Vol 1

I always liked Mark Waid. He's a solid comics writer well grounded in characters' history, and prepared to take a refreshing look at them from new angles, and to introduce some surprises in his stories. He's not quite in the Moore - Gaiman - Morrison league, but always enjoyable, so perhaps a notch below that top tier, pretty much like Peter David (IMO).

So I had high hopes for his Daredevil. And I wasn't really disappointed. This book starts off with Daredevil crashing a Mob wedding to stop a kidnapping by the dimension-jumping Spot. Paolo Rivera's art for this chapter is especially nice – and reminds me a bit of David Mazzucchelli, possibly because of how he depicts DD's body in motion (and possibly also from how he spots the shadows on it) dramatically but not overly flashy, making it look positively naturalistic by Marvel standards.

Waid then proceeds to give a solution how to move on from DD's secret identity having been outed previously – in this internet/paparazzi age, memes like that tend to lose power over time, so the notion that Matt Murdock is really Daredevil is now in the "some people are sure of it, others don't really know" category. Clever, if not earth-shattering, and opening up a nice venue of subplots and clever story details.

Since everybody now knows – or "knows" – that Matt Murdock is Daredevil, his legal career goes down the drain, because, well, somehow the prosecutor working the word "Daredevil" into every other sentence makes it impossible for Matt to win cases. I'm not really with Waid on how this works, actually, but I'll go along with it for the sake of the story. It's because Waid is a good writer that I'll, as a reader, choose to go along, but it's also a mark of how he's not top-notch (to me, at least) that I'll still have reservations. I've followed – for example – Grant Morrison along on far less logical story developments, but that's because with Grant Morrison, I'm usually just swept along with the inexorable flow of brilliant storytelling.

Anyway, Matt Murdock comes up with a new way of helping people, now that he can't be their lawyer: he'll teach them how to represent themselves, and coach them towards victory. This is, again, clever, and actually reminded me of the feeling I got when reading my very first DD story many, many years ago, with Stan Lee depicting a Matt Murdock able to come up with a clever way of helping his client, regardless of what conventional wisdom said.

So far, so good. What about the actual action? Well, DD faces two menaces in this collection. The first is a new take on a classic Marvel villain (again, in keeping with Waid tradition), the second a somewhat more prosaic criminal/superterrorist organization(s) threat against a – get this – blind kid. Of course Daredevil has to get involved. And they bring in the Bruiser, who's out to show he can take on all sorts of lower-lever superbeings in the Marvel Universe, crossing them of his (smartphone – another nice touch) list as he beats them, one after one. (DD is just above Spider-Woman on that list, something Bruiser regrets after handily beating DD in their first encounter.)

On the art: Paolo Rivera is the artist for the first half of the book, and as noted does an excellent job. Marcos Martin does the second half, and his figure and action drawing is excellent as well, but he needs to work on his faces – they're too cartoony, and not in an elegant cartoony style either, unfortunately. It's not terrible, but there's plenty of room for improvement.

Anyway, I'll give away a bit of the ending because it speaks to a larger point I've been making: the showdown with the conglomerate of criminal organizations is resolved with some clever lawyeristic wrangling by Daredevil – but I don't really buy it, because I can see the counter-argument to the point DD is (successfully) making to the crooks. Had it been Moore, Miller etc writing the story, I can well see how I'd be carried along by the strength of the narrative and/or the cleverness of how the argument is formulated, but that doesn't happen with Waid. He's merely in the "damned good" category of writers for me, not quite in the "superstars" one.

But you know what? "Damned good" is still damned good, and this book has plenty of clever and just plain good things going for it. This is excellent superhero fare. Heartily recommended.

(Second opinion: Comics Alliance has a good review of the book here, which among other things points to how Daredevil gives a little smile when he's about to throw himself into a fight against tough odds, giving emphasis to his "daredevil" moniker. Good catch, that.)

So I had high hopes for his Daredevil. And I wasn't really disappointed. This book starts off with Daredevil crashing a Mob wedding to stop a kidnapping by the dimension-jumping Spot. Paolo Rivera's art for this chapter is especially nice – and reminds me a bit of David Mazzucchelli, possibly because of how he depicts DD's body in motion (and possibly also from how he spots the shadows on it) dramatically but not overly flashy, making it look positively naturalistic by Marvel standards.

Waid then proceeds to give a solution how to move on from DD's secret identity having been outed previously – in this internet/paparazzi age, memes like that tend to lose power over time, so the notion that Matt Murdock is really Daredevil is now in the "some people are sure of it, others don't really know" category. Clever, if not earth-shattering, and opening up a nice venue of subplots and clever story details.

Since everybody now knows – or "knows" – that Matt Murdock is Daredevil, his legal career goes down the drain, because, well, somehow the prosecutor working the word "Daredevil" into every other sentence makes it impossible for Matt to win cases. I'm not really with Waid on how this works, actually, but I'll go along with it for the sake of the story. It's because Waid is a good writer that I'll, as a reader, choose to go along, but it's also a mark of how he's not top-notch (to me, at least) that I'll still have reservations. I've followed – for example – Grant Morrison along on far less logical story developments, but that's because with Grant Morrison, I'm usually just swept along with the inexorable flow of brilliant storytelling.

Anyway, Matt Murdock comes up with a new way of helping people, now that he can't be their lawyer: he'll teach them how to represent themselves, and coach them towards victory. This is, again, clever, and actually reminded me of the feeling I got when reading my very first DD story many, many years ago, with Stan Lee depicting a Matt Murdock able to come up with a clever way of helping his client, regardless of what conventional wisdom said.

So far, so good. What about the actual action? Well, DD faces two menaces in this collection. The first is a new take on a classic Marvel villain (again, in keeping with Waid tradition), the second a somewhat more prosaic criminal/superterrorist organization(s) threat against a – get this – blind kid. Of course Daredevil has to get involved. And they bring in the Bruiser, who's out to show he can take on all sorts of lower-lever superbeings in the Marvel Universe, crossing them of his (smartphone – another nice touch) list as he beats them, one after one. (DD is just above Spider-Woman on that list, something Bruiser regrets after handily beating DD in their first encounter.)

On the art: Paolo Rivera is the artist for the first half of the book, and as noted does an excellent job. Marcos Martin does the second half, and his figure and action drawing is excellent as well, but he needs to work on his faces – they're too cartoony, and not in an elegant cartoony style either, unfortunately. It's not terrible, but there's plenty of room for improvement.

Anyway, I'll give away a bit of the ending because it speaks to a larger point I've been making: the showdown with the conglomerate of criminal organizations is resolved with some clever lawyeristic wrangling by Daredevil – but I don't really buy it, because I can see the counter-argument to the point DD is (successfully) making to the crooks. Had it been Moore, Miller etc writing the story, I can well see how I'd be carried along by the strength of the narrative and/or the cleverness of how the argument is formulated, but that doesn't happen with Waid. He's merely in the "damned good" category of writers for me, not quite in the "superstars" one.

But you know what? "Damned good" is still damned good, and this book has plenty of clever and just plain good things going for it. This is excellent superhero fare. Heartily recommended.

(Second opinion: Comics Alliance has a good review of the book here, which among other things points to how Daredevil gives a little smile when he's about to throw himself into a fight against tough odds, giving emphasis to his "daredevil" moniker. Good catch, that.)

onsdag 14 november 2012

Vicki Scott & Paige Braddock: It's Tokyo, Charlie Brown

You know those old Peanuts movies and specials? Those that basically took a bunch of gags from the strip and strung them together to form part of the movie, and then had the plot sort of develop from there?

Well, that is pretty much what this is, albeit in comics format. Writer-penciller Vicki Scott starts off the book with some baseball gags from the strip, emphasizing Charlie Brown's lack of skill and his team's lack of success, and then throws in the kicker: the kids become selected as goodwill ambassadors in the president's "Young Ambassadors Program", and will travel to Japan to play baseball against another kids team.

That sets the stage for the gags and character interactions to follow. Marcie reads the guidebook to Japan, learning more about the country and teaching her friends a little about it in the process, Charlie Brown gets caught up in the moment and makes nice speeches to his friends about their responsibilities as goodwill ambassadors and nobody listens to him, and Woodstock gets mugged by the food in the Japanese restaurants they visit. Finally, the play baseball against a Japanese kids' team, and play at their usual level of competence (especially Charlie Brown), and Scott throws in a plot twist to keep it all from becoming an unhappy ending.

All in all, this really is an excellent Peanuts TV special. I won't compare it to Schulz' strip – really, how could you? – but it's a good, entertaining story with some nice touches and that is faithful to Schulz's characters. It's 100 pages, and I thought it was well worth my time reading them. Recommended.

Well, that is pretty much what this is, albeit in comics format. Writer-penciller Vicki Scott starts off the book with some baseball gags from the strip, emphasizing Charlie Brown's lack of skill and his team's lack of success, and then throws in the kicker: the kids become selected as goodwill ambassadors in the president's "Young Ambassadors Program", and will travel to Japan to play baseball against another kids team.

That sets the stage for the gags and character interactions to follow. Marcie reads the guidebook to Japan, learning more about the country and teaching her friends a little about it in the process, Charlie Brown gets caught up in the moment and makes nice speeches to his friends about their responsibilities as goodwill ambassadors and nobody listens to him, and Woodstock gets mugged by the food in the Japanese restaurants they visit. Finally, the play baseball against a Japanese kids' team, and play at their usual level of competence (especially Charlie Brown), and Scott throws in a plot twist to keep it all from becoming an unhappy ending.

All in all, this really is an excellent Peanuts TV special. I won't compare it to Schulz' strip – really, how could you? – but it's a good, entertaining story with some nice touches and that is faithful to Schulz's characters. It's 100 pages, and I thought it was well worth my time reading them. Recommended.

måndag 12 november 2012

Back from the comics store, November 2012 edition

Mutts – I've always liked Mutts (well, I loved it for the first coupla years), the Hägar and Wizard of Id collections are classic daily strips, Mort Drucker is only like the best MAD artist ever, and Gray Morrow is also a classic artist.

I love Peanuts, and while the comic book isn't really Schulz quality (how could it be, honestly?), this was a good issue with some well done stories, Buz Sawyer is a classic, and in 1945-46 not yet the somewhat dull Cold War strip it would become later, Neal Adams is the superhero artist even if he doesn't today have/use the smooth, elegant line of the 70s Neal Adams and I fully expect the writing to be... not the best possible, the Avengers book is written by Kurt Busiek whose work I've always liked (it was nice when the rest of the world caught up so he could get more work), and the Essentials and Showcase volumes are a good way of getting old comics that are in no way worth what it would cost to buy the original comic books.

Aaaand finally it's more Peanuts, Joe Kubert's lovely art in Sgt. Rock, I've always liked the Justice League – and the art of Alan Davis, and it's very nice to see classic EC work by legends Wallace Wood and Harvey Kurtzman in affordable format. I will enjoy reading this lot.

söndag 14 oktober 2012

Back from the comics store, October 2012 edition

I also got my monthly comics package down at my comics shop, Prisfyndet, a couple of weeks ago. With my editors throwing work at me, it'll be a while before I get to read this stuff (worst part is, I suspect they're giving me work not because they think I do a good job, but because they want to stop me from having time to read and enjoy myself).

I get all the Showcases; it's comics history in cheap packages – if not always all that great comics history – much like the Marvel Essentials. James Robinson's Starman is excellent and the omnibuses are a cheap-and-easy way of getting them. I love Peanuts, so I'm getting the new (kids) stuff even though it's nowhere near Shultz's truly magnificent strip. Barbara is by manga legend Osamu Tezuka, and thus pretty much mandatory. Mark Waid (Daredevil) is a good, solid superhero writer – not quite as outré as superstars like Grant Morrison, but delivering solid stories with good twists. Girl Genius is by almost-always-funny Phil Foglio, who holds the distinction of having created practically the only pornographic comics worth reading (Xxxenophile Tales). Neil Gaiman's Death stories are among the best stuff he's done, it's pleasantly free from the slight hint of pretentiousness that sometimes creeps into his Sandman stories, and the art by Chris Bachalo is excellent. Get it if you haven't already.

This lot is a quartet of classic newspaper strips. For the archives-I-hope-to-read-soon shelf.

Finally, in IDW's great-but-damn-it's-expensive Artist's Edition series, one of the truly great: Joe Kubert. It's gorgeous, but maybe you should settle for a somewhat cheaper collection instead of this oversized one. This one hurt...

This lot is a quartet of classic newspaper strips. For the archives-I-hope-to-read-soon shelf.

Finally, in IDW's great-but-damn-it's-expensive Artist's Edition series, one of the truly great: Joe Kubert. It's gorgeous, but maybe you should settle for a somewhat cheaper collection instead of this oversized one. This one hurt...

Back from the comics store, September edition

So anyway, I got some stuff at the Gothenburg book fair, now that I have a house to put it in.

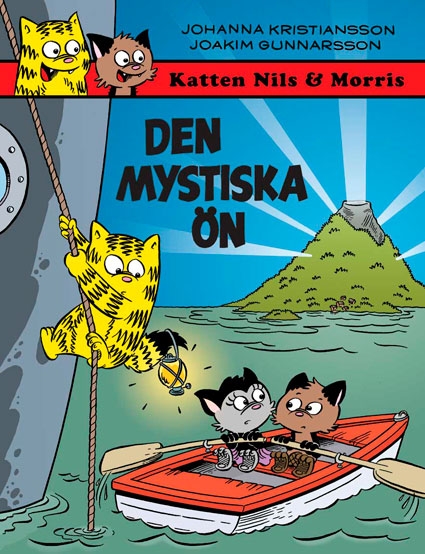

Li Österberg's stuff is always good. I prefer when she writes her own stories, but Patrik Rochling's scripts are very good, and make the people depicted in the stories people, instead of just characters in a story. Norwegian Jason is likewise always good, but I tend to only buy his stuff when it's on sale, as the hardcover editions are quite a bit on the pricey. Kvarnby serier contains comics by people who're studying a two-year course in the art/trade of making comics. And Den mystiska ön is and excellent adventure story for kids, reviewed here.

I bought some regular books as well; the Italian Renaissance is almost always enjoyable stuff, and I've always like the classical Dutch paintings. You can't go wrong with a huge book on evolution (unless, perhaps, if you're a teacher in some southern U.S. states), and I don't know much about horses, so why not get a book about them? Döda rummet is a pun on August Strindberg's classic novel Röda rummet, and an enjoyable fantasy by Per Demervall and Ola Skogäng about an alternative present where a cult has grown around the dead Strindberg... Or is he really dead? And Corto Maltese is of course a classic (although in my honest opinion, a somewhat overrated one).

This pic turned out crappy and does no justice to the four first volumes of the collected Duck works of Don Rosa, the brilliant writer-artist who unfortunately isn't doing any more stories because he's fed up with the lousy renumeration from the Disney juggernaut (I should add that the Swedish publisher of his works treat him pretty decently, though, as far as I know). Seriously, if you haven't read his stuff, you should – he's more or less the modern (or post-modern) Barks. I got these ones signed, and a sketch in one of them too – ha! Valhalla is an excellent album series by Dane Peter Madsen and his collaborators – though to be honest, it's just good a couple of albums into the series, and only excellent from about album 5-6 or so. This is the fourth collection of three albums, so it's well into the "excellent" phase. You gonna start reading this series, and you should, collection 3 containing albums 7-9 is the place to start, and you can expand your collection from there. Kiki of Montparnasse has received quite a lot of accolades, but I haven't had the time to read it yet.

Uti vår hage is a brilliant mixture of inspired silliness and crazy slapstick, sort of the Marx Brothers on steroids and in comics format. Well recommended. Zits is a modern classic (and I got my copy for free for having translated it). Elvis is also a bit of a modern classic here in Sweden, looking askance and through the eyes of a somewhat obnoxious anthropomorphic tortoise at the daily drudgery of modern (family) life. It's done by real-life couple Tony and Maria Cronstam, and you have to wonder exactly how much of it is from their own life, and to what extent they're just inspired by and/or extrapolationg from their own life. The strip is mainly played for laughs, but does occasionally delve into social commentary as well – which on one occasion seemed to flummox some less-than-competent critics who actually believed that the Cronstams were laughing at wife abuse, when it was simply the critics who were too stuck in their own prejudices about the Elvis strip to understand that particular strip. (I mean, good grief – seriously, a critic owes the works and artists/writers he reviews the courtesy of actually trying to understand what they're trying to say.) And finally, Norwegian Arild Midthun is a talented artist whose duck art reminds me quite a bit of the old master Vicar.

Li Österberg's stuff is always good. I prefer when she writes her own stories, but Patrik Rochling's scripts are very good, and make the people depicted in the stories people, instead of just characters in a story. Norwegian Jason is likewise always good, but I tend to only buy his stuff when it's on sale, as the hardcover editions are quite a bit on the pricey. Kvarnby serier contains comics by people who're studying a two-year course in the art/trade of making comics. And Den mystiska ön is and excellent adventure story for kids, reviewed here.

I bought some regular books as well; the Italian Renaissance is almost always enjoyable stuff, and I've always like the classical Dutch paintings. You can't go wrong with a huge book on evolution (unless, perhaps, if you're a teacher in some southern U.S. states), and I don't know much about horses, so why not get a book about them? Döda rummet is a pun on August Strindberg's classic novel Röda rummet, and an enjoyable fantasy by Per Demervall and Ola Skogäng about an alternative present where a cult has grown around the dead Strindberg... Or is he really dead? And Corto Maltese is of course a classic (although in my honest opinion, a somewhat overrated one).

This pic turned out crappy and does no justice to the four first volumes of the collected Duck works of Don Rosa, the brilliant writer-artist who unfortunately isn't doing any more stories because he's fed up with the lousy renumeration from the Disney juggernaut (I should add that the Swedish publisher of his works treat him pretty decently, though, as far as I know). Seriously, if you haven't read his stuff, you should – he's more or less the modern (or post-modern) Barks. I got these ones signed, and a sketch in one of them too – ha! Valhalla is an excellent album series by Dane Peter Madsen and his collaborators – though to be honest, it's just good a couple of albums into the series, and only excellent from about album 5-6 or so. This is the fourth collection of three albums, so it's well into the "excellent" phase. You gonna start reading this series, and you should, collection 3 containing albums 7-9 is the place to start, and you can expand your collection from there. Kiki of Montparnasse has received quite a lot of accolades, but I haven't had the time to read it yet.

Uti vår hage is a brilliant mixture of inspired silliness and crazy slapstick, sort of the Marx Brothers on steroids and in comics format. Well recommended. Zits is a modern classic (and I got my copy for free for having translated it). Elvis is also a bit of a modern classic here in Sweden, looking askance and through the eyes of a somewhat obnoxious anthropomorphic tortoise at the daily drudgery of modern (family) life. It's done by real-life couple Tony and Maria Cronstam, and you have to wonder exactly how much of it is from their own life, and to what extent they're just inspired by and/or extrapolationg from their own life. The strip is mainly played for laughs, but does occasionally delve into social commentary as well – which on one occasion seemed to flummox some less-than-competent critics who actually believed that the Cronstams were laughing at wife abuse, when it was simply the critics who were too stuck in their own prejudices about the Elvis strip to understand that particular strip. (I mean, good grief – seriously, a critic owes the works and artists/writers he reviews the courtesy of actually trying to understand what they're trying to say.) And finally, Norwegian Arild Midthun is a talented artist whose duck art reminds me quite a bit of the old master Vicar.

torsdag 11 oktober 2012

Johanna Kristiansson and Joakim Gunnarsson: Katten Nils & Morris – Den mystiska ön ("Nils the Cat & Morris – The mysterious island")

Yes, there hasn't been much happening on this blog for quite a while now. The main reason for that is that I moved and was rather worn out after moving about 140 shelf meters of comics, 60 shelf meters of books, and assorted other stuff that tends to accumulate as the years pass, and then trying to fit them into my new home in some sort of working order. (Haven't really succeeded with that part yet, I must confess.)

But having done at least the most necessary parts of getting the new house functional for my needs (se enclosed pictures at bottom of page), it is time to get some blogging going again. We'll start with an excellent children's comic by Joakim Gunnarsson and Johanna Kristiansson: Katten Nils & Morris – Den mystiska ön. If I understand things correctly, Gunnarsson is mostly responsible for the script and Kristiansson for the art.

Katten Nils – or, Nils the Cat – is a very popular comic strip in the Swedish children's magazine Kamratposten. Nils himself is not very intelligent, to say the least, but the strip's exploring of themes important to kids (mainly friendship and love, judging from the sample strips I've seen from it) has mightily endeared both him and the strip to Kamratposten's readers. Now, Gunnarsson and Kristiansson have staked out new ground with a book-length story about Nils and his best friend Morris joining cat-girl Semlan (who is in love with Morris and quite a bit bothersome, in Morris' opinion) on a ship to Semlan's aunt's coffe bean-producing island. The island is home to a volcano that threatens to erupt, so it's important to save as many coffee beans as possible. Semlan doesn't really want Nils coming along to disrupt her plans for some quality time with Morris, whereas Morris wants Nils coming along to disrupt any plans Semlan may have for quality time with him. And the adventure moves briskly along from there...

I was just a little bit wary of the depiction of Semlan at first, what with her being more interested in boys (well, Morris, at least – Nils seems a bit too loutish for her) and relationships rather than adventures. Now, I do think it's perfectly OK for both girls and boys to have different preferences, whether it's for adventure or for relationship stuff (and that it's more than a little bit stupid to try and force them to change their preferences based on what's the current fashion in society for what they "should" prefer), but I was a bit worried that Semlan come off as merely the classical girly stereotype – of which I've seen enough in many, many comics and movie stories already. Fortunately, I was proven wrong.

Not only are Semlan's feelings for Morris depicted with a lot of respect and compassion, both for the character and for those feelings, but she gets to show herself to be brave and knowledgeable in a manner that not only surprises Morris but also heightens his respect for her as a person. It works very well, and offers a nice model for the book's young readers how to treat others. (It's a nice model for grown-ups as well, but they're usually already too set in their ways to change, so if they're inclined to go with their prejudices rather than keeping an open mind towards others, reading a children's comic is hardly going to change that one iota.)

Now, I know Joakim Gunnarsson, so I know that he's an old comics fan-turned-pro and also quite the Bamse and Carl Barks aficionado – and it shows in the story. Not only is it a classical Bamse or Uncle Scrooge (albeit a little bit "childified" compared to the Barks variety) plot, but there are several Barksian references in the script as well. It works very well if you catch those references, and doesn't detract from the story if you don't.

I don't really know Johanna Kristiansson, I just met her briefly at this year's annual book fair in Gothenburg, so I can only say that she seems to be just about the nicest, most utterly charming person you could imagine, and that she does an excellent job with the art for this story. Kristiansson makes the characters move and emote with flair and gusto – vitally important for depicting both the adventure and emotions/relations aspects of the story.

This is a great children's book, and sufficiently well done that it isn't a waste of time for adult readers, either – even though they'll probably have to rely quite a bit on the child within to appreciate it, as it is pretty clearly a story aimed at kids.

Recommended.

And finally, as promised, a couple of examples of the interior decoration of my new home:

But having done at least the most necessary parts of getting the new house functional for my needs (se enclosed pictures at bottom of page), it is time to get some blogging going again. We'll start with an excellent children's comic by Joakim Gunnarsson and Johanna Kristiansson: Katten Nils & Morris – Den mystiska ön. If I understand things correctly, Gunnarsson is mostly responsible for the script and Kristiansson for the art.

Katten Nils – or, Nils the Cat – is a very popular comic strip in the Swedish children's magazine Kamratposten. Nils himself is not very intelligent, to say the least, but the strip's exploring of themes important to kids (mainly friendship and love, judging from the sample strips I've seen from it) has mightily endeared both him and the strip to Kamratposten's readers. Now, Gunnarsson and Kristiansson have staked out new ground with a book-length story about Nils and his best friend Morris joining cat-girl Semlan (who is in love with Morris and quite a bit bothersome, in Morris' opinion) on a ship to Semlan's aunt's coffe bean-producing island. The island is home to a volcano that threatens to erupt, so it's important to save as many coffee beans as possible. Semlan doesn't really want Nils coming along to disrupt her plans for some quality time with Morris, whereas Morris wants Nils coming along to disrupt any plans Semlan may have for quality time with him. And the adventure moves briskly along from there...

I was just a little bit wary of the depiction of Semlan at first, what with her being more interested in boys (well, Morris, at least – Nils seems a bit too loutish for her) and relationships rather than adventures. Now, I do think it's perfectly OK for both girls and boys to have different preferences, whether it's for adventure or for relationship stuff (and that it's more than a little bit stupid to try and force them to change their preferences based on what's the current fashion in society for what they "should" prefer), but I was a bit worried that Semlan come off as merely the classical girly stereotype – of which I've seen enough in many, many comics and movie stories already. Fortunately, I was proven wrong.

Not only are Semlan's feelings for Morris depicted with a lot of respect and compassion, both for the character and for those feelings, but she gets to show herself to be brave and knowledgeable in a manner that not only surprises Morris but also heightens his respect for her as a person. It works very well, and offers a nice model for the book's young readers how to treat others. (It's a nice model for grown-ups as well, but they're usually already too set in their ways to change, so if they're inclined to go with their prejudices rather than keeping an open mind towards others, reading a children's comic is hardly going to change that one iota.)

Now, I know Joakim Gunnarsson, so I know that he's an old comics fan-turned-pro and also quite the Bamse and Carl Barks aficionado – and it shows in the story. Not only is it a classical Bamse or Uncle Scrooge (albeit a little bit "childified" compared to the Barks variety) plot, but there are several Barksian references in the script as well. It works very well if you catch those references, and doesn't detract from the story if you don't.

I don't really know Johanna Kristiansson, I just met her briefly at this year's annual book fair in Gothenburg, so I can only say that she seems to be just about the nicest, most utterly charming person you could imagine, and that she does an excellent job with the art for this story. Kristiansson makes the characters move and emote with flair and gusto – vitally important for depicting both the adventure and emotions/relations aspects of the story.

This is a great children's book, and sufficiently well done that it isn't a waste of time for adult readers, either – even though they'll probably have to rely quite a bit on the child within to appreciate it, as it is pretty clearly a story aimed at kids.

Recommended.

And finally, as promised, a couple of examples of the interior decoration of my new home:

lördag 21 juli 2012

Sven Oskarsson & Sten Widmalm (ed.): Myt eller verklighet? Om samband mellan demokrati och ekonomisk tillväxt ("Myth or reality? On connections between democracy and economic growth")

I've been rather remiss in my blogging lately, which is connected with my efforts to find and buy a house I can afford as well as preparing to move into it. Anyway, I'll try to get some quickie reviews done. First up, another book on the democracy.

This is a book by people used to teaching students, and it shows in its didactic structure. The first chapter gives a quick overview of various theories of modernity - development - democracy. Second chapter takes a closer look at a specific theory of modernization, pioneered by Seymour Martin Lipset: that economic growth leads to socioeconomic changes which will lead to increasingly democratic rule. Then follows a couple of chapters on the general empirical support for the theory, a half-dozen or so chapters looking at various countries from the perspective of the theory, and a final chapter summarizing the findings of the book.

First off, the theory argues, economic modernization will change the class structure of society, creating a growing and more affluent middle class. It'll also lead to improved education and a better educated population, which'll lead to democratic values rooting themselves more firmly among more citizens. Education furthers the growth of more tolerant norms and reduces the attraction of anti-democratic extremist parties. Third, economic development strengthens civilian society, leading to more non-government, voluntary organizations that keep a check on elected power (and also teaches democratic values).

The correlation has been shown in empirical research to be quite quite clear and statistically rather weak. So the theory has met with a lot of criticism, and efforts have been made to deal with that criticism. One research approach has involved looking at the degree of socio-economic modernization, not just looking at GNP per capita, which has often been used as a proxy variable for modernization/economic development. And modernization can't just involve increased per capita incomes, it also requires that the increased wealth is somewhat equitably shared among the citizens of the country.

Turns out that when you take that variable into account, the theory gets that much stronger. Not only do countries with a more equal distribution of income tend to be more democratic, when combined with more equality, increased wealth also tends to correlate with increased tolerance towards various minorities (like homosexuals and immigrants).

The third chapter looks closer at this aspect and concludes that democracy will be more common among nations where the market economy won't result in very large economic disparities, where the costs of repression are high and where the tax base is comparatively mobile (which'll lead governments to refrain from overtaxing it, thus reducing the incentive for it to embrace anti-democratic methods to protect its wealth.

There's more in this book that's worth reading (although the chapters devoted to case studies of countries like France, Russia etc didn't do much for me as they mostly merely illustrated the theory and gave short overvies of those countries' recent political history – not a bad thing, but not really giving me any deeper insights into the theory and its empirical support or lack thereof).

Definitely worth your time if you can read Swedish. Recommended.

This is a book by people used to teaching students, and it shows in its didactic structure. The first chapter gives a quick overview of various theories of modernity - development - democracy. Second chapter takes a closer look at a specific theory of modernization, pioneered by Seymour Martin Lipset: that economic growth leads to socioeconomic changes which will lead to increasingly democratic rule. Then follows a couple of chapters on the general empirical support for the theory, a half-dozen or so chapters looking at various countries from the perspective of the theory, and a final chapter summarizing the findings of the book.

First off, the theory argues, economic modernization will change the class structure of society, creating a growing and more affluent middle class. It'll also lead to improved education and a better educated population, which'll lead to democratic values rooting themselves more firmly among more citizens. Education furthers the growth of more tolerant norms and reduces the attraction of anti-democratic extremist parties. Third, economic development strengthens civilian society, leading to more non-government, voluntary organizations that keep a check on elected power (and also teaches democratic values).

The correlation has been shown in empirical research to be quite quite clear and statistically rather weak. So the theory has met with a lot of criticism, and efforts have been made to deal with that criticism. One research approach has involved looking at the degree of socio-economic modernization, not just looking at GNP per capita, which has often been used as a proxy variable for modernization/economic development. And modernization can't just involve increased per capita incomes, it also requires that the increased wealth is somewhat equitably shared among the citizens of the country.

Turns out that when you take that variable into account, the theory gets that much stronger. Not only do countries with a more equal distribution of income tend to be more democratic, when combined with more equality, increased wealth also tends to correlate with increased tolerance towards various minorities (like homosexuals and immigrants).

The third chapter looks closer at this aspect and concludes that democracy will be more common among nations where the market economy won't result in very large economic disparities, where the costs of repression are high and where the tax base is comparatively mobile (which'll lead governments to refrain from overtaxing it, thus reducing the incentive for it to embrace anti-democratic methods to protect its wealth.

There's more in this book that's worth reading (although the chapters devoted to case studies of countries like France, Russia etc didn't do much for me as they mostly merely illustrated the theory and gave short overvies of those countries' recent political history – not a bad thing, but not really giving me any deeper insights into the theory and its empirical support or lack thereof).

Definitely worth your time if you can read Swedish. Recommended.

söndag 8 juli 2012

onsdag 4 juli 2012

lördag 30 juni 2012

Back from the comics store, June 29 edition

Lots of nice stuff this month. I'm still working my way through Showcase Presents Batman 1-3, though, so it'll have to wait.

(Actually, I'm almost finished with #3. Carmine Infantino did a very good Batman, nicely inked by reliable old hand Joe Giella. Unfortunately, his Batman isn't the most common version in these books, but at least Giella's inks can be relied on to add a modicum of elegance to even rather inelegant pencil drawings.)

I did this!

Translated it, that is.

I always like to translate Zits because it's such a good strip. This is the second collection, and while it's not yet quite yet the excellent strip it's going to be later on, it's well on its way there and well worth anybody's time. My hat is definitely off to Jim Borgman & Jerry Scott for their good work.

Published by Ekholm & Tegebjer.

I always like to translate Zits because it's such a good strip. This is the second collection, and while it's not yet quite yet the excellent strip it's going to be later on, it's well on its way there and well worth anybody's time. My hat is definitely off to Jim Borgman & Jerry Scott for their good work.

Published by Ekholm & Tegebjer.

fredag 29 juni 2012

Rabasa, Pettyjohn, Ghez & Boucek: Deradicalizing Islamist Extremists

I'm not a believer in the "The Muslims are coming! Western Civilization is under threat!" rallying cry of various bigots and xenophobes – the ultimate expression of which could be seen in the horrors of the massacre in Norway – but you don't have to belong to that crowd to consider violent Islamist radicals a problem. Terrorism is no more acceptable from the Right, Left, Muslims or Christians etc – it's terrorism, plain and simple, and I find all sorts of flirting with political violence highly distasteful. So, techniques for deradicalizing extremists of all stripes would seem to be a field of study well worth pursuing.

This book, by Angel Rabasa, Stacie Pettyjohn, Jeremy Ghez and Christopher Boucek does just that.

The basic premise is simple. There are a number of people who've been apprehended as terrorists where radical islamism has been a prime motivator in their actions. How have various countries tried to defuse the danger that these people pose to society?

The authors come to that subject armed with strategies and knowledge that has previously been gathered about and used on radicals of other political stripes. The general problem is getting violent radicals to disengage from violent groups and leave violent strategies behind. In order to do so more reliably, the authors argue, it is better if one can also deradicalize them, as somebody who leaves a violent group but is still a radical may well return to his/her violent ways later on, if they get an opportunity to do so.

This book, by Angel Rabasa, Stacie Pettyjohn, Jeremy Ghez and Christopher Boucek does just that.

The basic premise is simple. There are a number of people who've been apprehended as terrorists where radical islamism has been a prime motivator in their actions. How have various countries tried to defuse the danger that these people pose to society?

The authors come to that subject armed with strategies and knowledge that has previously been gathered about and used on radicals of other political stripes. The general problem is getting violent radicals to disengage from violent groups and leave violent strategies behind. In order to do so more reliably, the authors argue, it is better if one can also deradicalize them, as somebody who leaves a violent group but is still a radical may well return to his/her violent ways later on, if they get an opportunity to do so.

Rabasa et al draw on studies of people who leave gangs, criminal organizations, cults, sects and terrorist organizations to draw the following conclusions:

Individual disengagement is usually a consequence of a trigger, usually a traumatic or violent event. When that trigger occurs, it is crucial that there be support available for the individual to leave the group, or it might instead strengthen his/her commitment to it. So when a militant is captured, for example – a traumatic event – this may precipitate a cognitive opening, and that opportunity should be utilized.

Second, governments can influence the cost/benefit analysis of staying in or leaving an organization. This can be done by implementing counterterrorism measures while offering incentives to increase the benefits of exiting. Repression alone often backfires and causes further radicalization.

Third, individual commitment to the organization and its cause is an important factor. There are affective, pragmatic and ideological bonds to overcome. The individual has formed emotional attachments to the organization and its members, receives practical benefits from that membership, and has a loyalty to the group's ideology.

This latter part is important when dealing with religious groups, and often necessitates theologically skilled people who can confront members' beliefs and show them other interpretations of their religion which are incompatible with the crimes they've been committing as members of the organization. Most Middle Eastern and Southeast Asian programs of disengagement and deradicalization use mainstream scholars and former radicals to engage radical extremists in discussions of Islamic theology for this purpose.

The authors examine prison-based programs for individual rehabilitation. Basically, a full such program includes the theological component, support for the prisoner's family (so that they feel that society isn't casting them out but is in fact trying to help them), having the prisoner learning a job so that he can support himself and his family when he gets out, having the community take responsibility for him when he's released so that he feels he has a place in society, and religious instruction – as many "Islamist" radicals don't have a very thorough theological schooling, leaving them more free to use snippets of religion to justify their actions. It is thus critical that the state can find credible interlocutors to develop relationships with imprisoned militants to challenge their views. You also need a monitoring function post-release to ensure that radicals don't fall back to their old habits and friends on the radical fringe. (And, of course, some radicals just aren't interested in deradicalizing at all.)

Mainly, it's about rehabilitation, and the programs they sketch out – and which seem to be most completely enacted in places like Saudi Arabia and Singapore – seem well thought out and reasonable. Of course, you wish that such programs would exist for all prisoners in one's prison system, as the basic rationale of the programs seem applicable to all sorts of criminals and radicals. The chapter on European preventative programs also points out that it is important to address grievances that otherwise may motivate Muslim youths to consider Western society as not caring about them, leading to them not caring about society right back and perhaps radicalizing in response to indignities and maltreatment – of themselves and others.

The book gives an initial summary of these strategies for deradicalization, then moves on to reviews of individual-oriented deradicalization and disengagement programs in various Middle Eastern & Southeast Asian countries and of preventative deradicalization programs in Western Europe, and also of collective deradicalization and disengagement strategies – once an organization's leadership gets disaffected with violence, if they have sufficient "cred" with their members to convince them as well, you have a golden opportunity for collective deradicalization. And with good counterterrorism polices, terrorist organizations will eventually come to a possible turning point when they realize that "hey, this isn't working. We've been doing this for twenty years, and we haven't really accomplished anything". In the final chapter, you then get some implications and recommendations based on the findings of the book.

If you're short on time, practically all you need to read is the summary. The rest of the book deals mainly with how various countries have succeeded in implementing the strategies implied, and the recommendations chapter draws upon the strategies sketched out in the summary. My recommendation is to read the summary, then the first chapter – "Disengagement and deradicalization" – for a closer look at what the terms mean and imply, followed by the section dealing with how Singapore enacts is deradicalization program (as it seems the most fully implemented one), and finally close off with the Recommendations chapter.

This is a book well worth reading (though you can save a bit of time by following my "study guide" outlined above), but I do think you should keep a couple of things in mind when doing so: The strategies here are applicable not just to Muslims, because not just Muslims are susceptible to radicalization; all Muslims are not the same; and Islamist terrorism is not the greatest threat to the world today. It is an important issue, but we have many other sources of terrorism (I don't think Islamist terrorism is the most common one in Europe, for example) and many other societal problems that need to be dealt with. Just because Al-Qaida managed to commit a huge, coordinated atrocity in the US in 2001, and the US government then, after taking down the Afghanistani terrorist-tolerating government, went nuts and invaded Iraq, does not mean we have to focus narrowly on Islamist terrorism and radicalization – nor ignore it, of course.

That said, this is a good book for what it sets out to do: show strategies for preventing radicalization and facilitating people's exit from radical and violent organizations.

Worth a read, definitively, although most of the "this is how they do it in countries X, Y and Z" chapters can be read a bit more cursory IMO. Recommended.

lördag 23 juni 2012

Bud Grace: Hög klubba ("High-sticking")

Before Bud Grace made it big (especially in Scandinavia) with his Ernie/Piranha Club strip, he was a nuclear physicist. In between, he was a freelance cartoonist, getting published in various magazines. This is a collection of his cartoons from those days.

Grace's background as a physicist comes through in many cartoons depicting researchers and laboratories. (My favorite is the one about the researcher who blames her constant tardiness to meetings on Heisenberg's uncertainty principle.) Others depict themes that would recur in Ernie (albeit in milder forms), like men who can't get women and therefore date animals.

You can sort of tell that Grace hasn't quite found his niche yet with the cartoons of this volume. He seems to oscillate between going for a Playboyesque or perhaps Gahan Wilsonesque absurdity and the gross-out factor of Hustler cartoonists (I associate to Tom Cheney, but it's been so long since I read his work that I can't be certain that I don't misremember his style of jokes). There's also a cartoon or two that seems to be going for a Gary Larson-type humor, but that could be because of them both being inspired by the same American cartoon traditions. A lot of them are funny, a few are merely vulgar or do stuff that's really been done before. I enjoyed it but probably won't be in any rush to re-read it.

This is an amusing but not really great collection of cartoons; you'll probably laugh at some of them and not really care for some others. I think it's worth a read, at least. But if you're an Ernie/Piranha Club fan, of course you should read it to get a hunch about where Grace is coming from; this is the precursor to the sometimes-inspired silliness of the Ernie strip.

Almost-recommended.

Grace's background as a physicist comes through in many cartoons depicting researchers and laboratories. (My favorite is the one about the researcher who blames her constant tardiness to meetings on Heisenberg's uncertainty principle.) Others depict themes that would recur in Ernie (albeit in milder forms), like men who can't get women and therefore date animals.